After 42 Years, Memories of Vietnam War Still Raw for Many Vietnamese Living in the Washington D.C. Area

PBS Documentary, “The Vietnam War” Prompts Examination of Vietnamese Refugees’ Journey and Imprint on Local Area Communities

By Megan Nguyen Rummler

WASHINGTON — Even at the tender age of two, Kim Oanh Cook vividly recalls sitting in a “pousse-pousse,” the French word for a rickshaw, watching her house in North Vietnam burn. It is her earliest memory.

“I remember my mom running back and forth to the burning house, dumping items on me,” the 76-year-old recalls with bright, intense eyes.

Cook, a spry and petite Vietnamese woman with salt-and-pepper hair, is as complex as her country of origin. Her easy smile and laugh masks the intense and formidable stories that fill her traumatic upbringing.

“I remember I was sitting all by myself, my mom kept piling things on top of me and finally she said, ‘You must hang on to this; it is all we have now.’”

Cook, who first came to the United States in 1962 as a student, embodies a generation of Vietnamese refugees that survived the country’s lengthy and continuous struggle for independence against foreign invaders.

A long-time Falls Church, Virginia resident, Cook is among the nearly 2.1 million Vietnamese Americans currently living in the country, according to the 2016 United States Census Bureau. The Washington metropolitan area is home to approximately 70,000 Vietnamese people, a population that ranks sixth largest nationwide.

Documentary, Stirs Up Echoes of War

Heartbreaking loss, hate and conflicting struggle are central themes that have dominated Vietnam’s recent history for the last century.

These themes, along with emotions of anger, confusion, loss, grief and tragedy are among the complex nuances being explored in the recently released PBS documentary film, “The Vietnam War.”

For many Vietnamese Americans, as well as Vietnam war veterans nationwide, the film has triggered past memories, reopened old wounds and reignited intense discussion and debate surrounding the 20-year-long conflict.

Although widely praised in the mass media, the film was disappointing and underwhelming for many in the Vietnamese community locally and nationwide.

“My dad wanted more complexity,” said Thanh Tan in a telephone interview from Seattle, Washington. “He doesn’t feel like his story, as a South Vietnamese, was represented.” Tan’s father served as an officer in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam.

Tan, an award-winning journalist, hosts a new podcast called, “Second Wave,” which explores American stories born from the Vietnamese refugee experience.

She says the Vietnamese community voiced protests of the film on social media with statements such as: “This is fake news! It makes the South Vietnamese look bad! And, the producers are Communist sympathizers!”

“The film did not talk about the South Vietnamese and how they fought or even about their political efforts,” says Cook who fled Vietnam in 1973 and now lives in Virginia.

“We need the real history of Vietnam—not the history of Vietnam written by Americans, written by French, written by Communists.”

While acknowledging the effort made by filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick in the making of “The Vietnam War,” Cook and many other Vietnamese Americans say the film mostly triggered painful memories.

“I look up, and there was an airplane with leaflets raining from the sky,” she recalls with disbelief in her eyes. She says it was an American Allied airplane.

“This was my first vision of America.” Cook explains the dropped leaflets declared the Japanese had lost the war.

“Our house sat right on the river, and Japanese soldiers were killing themselves by jumping in the river—that I remember.”

During the country’s battle for independence from Japan, Cook’s childhood home was burned down on order by Ho Chi Minh, the leader of Vietnam, as part of a military tactic in late 1945. Known as the “Moscow-strategy” or “scorched-earth,” this military maneuver destroyed everything that an enemy might use while advancing through or withdrawing from a location.

Fundamental varying truths play a constant role in the discussion and debate around the conflict. There has even been wide debate over when the Vietnam War began.

“The Vietnam War didn’t start in 1967. That was a moment of great kinetic energy in the war, but it started long before that. And you could argue that it really started in 1945,” Novick, one of the filmmakers of “The Vietnam War,” said in a September interview with The Washington Times.

The Japanese occupied Vietnam in September 1940 and remained there until the end of World War II in August 1945. Japan formally surrendered to the American Allies on Sept. 2, 1945.

One truth that remains undeniable is that over 42 years have passed since the Fall of Saigon, and the war memories are as fresh and alive today as they were on April 30, 1975.

Vietnamese Refugees, First Wave

Toward the end of the conflict, Vietnamese refugees fled their country in two distinct waves.

According to the Immigration Policy Center, the first large wave occurred in 1975 and included an estimated 135,000 Vietnamese who were considered elites and were highly skilled.

The immigrants in this first wave were well educated and often had ties to the U.S. government.

“I had a university diploma and spoke English, so I was a translator for the Defense Attaché Office,” says Nga Thi Hua, a 72-year-old Vietnamese woman who lived in Washington, D.C., and Virginia 10 years ago, but now resides in Augusta, Georgia.

This group included lawyers and engineers, high-ranking Vietnamese officers and foreign-born brides.

For fear of political retribution, these refugees were evacuated first and airlifted by the U.S. government to bases in the Philippines, Wake Island and Guam. From there, they were transferred to temporary refugee camps at various military bases at Camp Pendleton, California; Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania; Fort Chaffee, Arkansas; and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida.

With already established connections to the American government and embassy, many Vietnamese settled in Northern Virginia because of its nearness to the nation’s capital and the availability of U.S. sponsor services, such as the Catholic Church. Catholic churches in Virginia often sponsored Vietnamese who were practicing Catholics.

“Catholic charities helped us a lot. My dad had no more than $200 in his pocket when we came here,” says Richard Nguyen, general manager of Nam Viet restaurant in Arlington, Virginia.

Vietnamese Refugees, Second Wave

As the first wave of Vietnamese refugees was beginning to acclimate in the Washington D.C. area, the second wave begins to evacuate between 1976 and 1995.

An estimated 800,000 Vietnamese people made a desperate and perilous escape by boat.

These refugees, known as “boat people,” were generally less educated than the previous wave of evacuees and did not have ties to the U.S. government.

“My old wooden boat was about 30 feet long by 10 feet wide,” said Reverend Dr. Min Van Lam, pastor at Vietnamese Gospel Baptist Church of Alexandria.

Lam’s vessel held the lives of 47 Vietnamese refugees: 24 men, 13 women and 10 children. The youngest passenger was a 20-month old girl. After nearly two days at sea, the boat was narrowly rescued on October 5, 1980, by a passing merchant ship.

Many other Vietnamese boat refugee attempts were futile. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, between 200,000 and 400,000 boat people perished at sea.

Home away from home

In 2003, a cultural heritage assessment report prepared for Arlington County stated that by the end of the Vietnam War, 15 percent, or 3,000, of the nation’s Vietnamese population, resided in the Washington, D.C. area.

The most densely settled Vietnamese areas in Northern Virginia ran along Wilson Boulevard and Columbia Pike, extending west toward Falls Church and Annandale. Known locally as Little Saigon, this neighborhood reached its peak during the late 1970s through the early 1980s.

“My first job was at age 13. I remember filling water glasses and being the busboy,” recalls Richard Nguyen. His parents own Nam Viet restaurant in Arlington, Virginia. The eatery is one of the last remaining original Vietnamese businesses in Clarendon and has been in business for over 30 years.

Little Saigon in Arlington remained a bustling Vietnamese community for nearly a decade. Vietnamese-owned retail and restaurants provided a sanctuary for Vietnamese immigrants that reminded them of home.

After the Washington D.C. Metro Railway was completed through Arlington, redevelopment and gentrification followed suit and landlords increased rents. Vietnamese business owners that couldn’t afford the increased prices became displaced. Little Saigon soon faded away.

Some voices in the Vietnamese business community claim alleged discrimination forced them out of Little Saigon. Others say the allure of a newer, much larger shopping center, a few miles westward, was too much to resist and left on their own.

Eden Center—opened in the 1980s—was the shiny new retail and commercial center located in nearby Falls Church, which features Vietnamese delis, restaurants, grocery, jewelry stores and an indoor shopping mall.

Today, its parking lot proudly flies the South Vietnamese flag alongside the American flag. It is considered the largest Vietnamese commercial space on the East Coast.

“It’s a place where we can go as a community and feel like we are in Vietnam without having to leave America,” says Emily Duong Giovinazzo, a 28-year old Vietnamese woman, who also holds the title of 2013 Miss Pacific Asian American.

As a public figure, Giovinazzo is very active in the Vietnamese and Asian American communities and often participates in yearly festivals and events at Eden Center that draw the Vietnamese community together.

Moving Forward, Steadily Healing Wounds

Locally, of the estimated 70,000 Vietnamese Americans living in the Washington, D.C. area, most have acclimated and are living content lives.

However, nationwide, recent figures show more than 233,000 Vietnamese Americans live in poverty, according to a 2011 report by Asian American Center for Advancing Justice.

“We find the numbers on poverty from our report truly paints the picture of how diverse and resource-deprived are some populations within our community,” says John Yang, president and executive director of Asians Americans Advancing Justice.

One lingering question is what portion of Vietnamese refugees are living in poverty, due in part, to the trauma experienced as a result of the war?

The theme of loss, struggle and conflict has indelibly left a lasting mark on the Vietnamese community in the Washington, D.C. region.

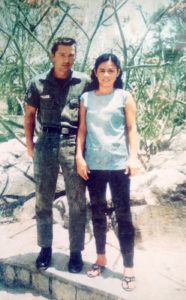

“My grandfather was an American pilot and sadly we don’t know who he is,” said Giovinazzo, the former Miss Pacific Asian American, who resides in Frederick, Maryland.

She explains her family left Vietnam in 1990 as part of The Amerasian Homecoming Act, which gave preferential immigration status to children in Vietnam born of U.S. fathers.

An estimated 23,000 Amerasians and 67,000 of their relatives entered the United States under this act.

Giovinazzo says her mother kept one photograph as a keepsake. She burned all other documents out of fear that the Vietcong might discover the relationship.

“The worst part is not knowing. In the picture, he’s wearing his pilot’s uniform, but we can’t read his name label because the angle is off. We are still searching,” sighs Giovinazzo.

Back in Falls Church, Cook spends her days devoted to her work as founder and executive director of the Vietnamese Resettlement Association (VRA)—a role she has proudly held for over 30 years.

VRA assists ethnically diverse low income refugees with health and welfare services.

When asked about her work and what keeps her moving forward, she imparts wise words for all refugees and immigrants struggling to assimilate.

“It is very tough here, but don’t give up. Don’t let the old country drain you of all your love, resources and attention that it leaves you feeling like a stranger in the only land that gave you one last chance.”

It is a breezy and sunny day. Cook beams as she tends to her backyard garden. The front door chime is blowing in the wind. Dozens of pots are filled with native Vietnamese flowers and fruit plants and sounds of trickling water from the koi pond fill the air.

“As long as I live, I will fight for myself and others,” she said. “Good earth will attract birds.”

“I am very lucky I live in an area where diversity is appreciated and that I have a place in the sun.”